Wear What You Love. Live With it Longer.

Breaking free from the conventional cycle of consumption is not only liberating, it’s a planetary imperative.

The truth is that retail therapy works. It's all tangled up with the promise of a fresh experience, a vision of how things could be. But the dopamine rush you get from making a purchase is long gone once you realize you have a home crammed full of things you don’t need and a closet stuffed with clothes you won’t wear. Cue the financial remorse and environmental guilt.

Americans have been shaped by post-World War II prosperity, an era in which mass consumption became a democratic virtue. No longer supplying the war effort, factories churned out appliances, fabrics and housewares. These modern conveniences were the reward for sacrifices made in the preceding years—to shop was to be a good citizen. The government even funded exhibitions at home and abroad showcasing the American way of life in the form of well-designed consumer goods. Today, we are repeatedly reminded that it’s up to us to spend and keep the economy afloat.

Times change. After years of industrial abundance, we’re now facing an environmental crisis that demands we reverse course. Even so, appreciating what you have for the resources that went into it and bucking the steady temptation for what's new and hot are as culturally radical as they are necessary.

So what’s in it for you? Shifting your relationship to what you own can be empowering.

“Consumer spending is responsible for about 70% of the nation's economic activity, and the retail industry overall has more jobs than any other business sector .”

—Chris Isidore, CNN Business

SIMPLICITY

You don't have to look long to discover there’s a groundswell of folks pursuing the simple life. The Minimalists Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus gave up lucrative careers and a slew of personal possessions to make space for more meaningful experiences. Julie O’Rourke, the designer behind the plant-dyed clothing line Rudy Jude, shares snapshots of her life on Instagram, such as the family handweaving a rug or her children tapping a tree for maple syrup, while husband Anthony Esteves documents the process of building their home by hand. Similarly, Brooklyn author (Simple Matters) and influencer (@readtealeaves) Erin Boyle practices all things slow and sustainable, from repairing an old toaster to hand sewing curtains.

It can all be a bit much. How many of us are really going to make our own possessions? I’d consider it a win if I found time to make my own meals—and this despite the Covid work-from-home revolution. But that’s actually the point. Most of us won’t achieve (aren’t even aiming for) a handcrafted reality, but we’d welcome a more intentional way of living. One where we’re not overwhelmed but enriched by what we possess, and where we waste less time, money and energy sorting through it.

Fortunately, the simplest choice is often the most versatile one. Do you need a toaster and a microwave when your oven already browns and warms? You’ll get far more mileage out of a dress you can wear many ways than a statement piece you’ll park between showings. That’s the appeal of the capsule wardrobe and its attendant challenges, like putting together looks from only 10 items for 10 days or turning out the same piece in a new way for 30 days running.

If you boil your purchases down to what you most need, you may just find yourself with more, not less—more counter space, more closet space, more to wear. It’s a new (old) way of thinking, and it changes the equation from sacrifice to abundance.

“In a world where with the click of a few buttons and the stroke of even fewer keys we can have at our doorsteps any number of conveniences, we buy too much, keep too much, equate stuff with happiness and happiness with stuff, and lose ourselves somewhere along the way. And this skewed relationship can make us feel very bad indeed.”

—Erin Boyle, Simple Matters: Living with Less and Ending Up with More

DURABILTY

Once you find something you love—a wool sweater that gets softer and cozier as the years go by, a well-seasoned cast iron skillet, a good-sitting sofa with just the right dimensions—holding on to it becomes important.

I find it every bit as exciting to restore something I own as it is to buy something shiny and new. The need for new things will never entirely go away, but it’s amazing just how much you can reduce it. Try creating wish lists and adding things you think you need. Check back in a month or three or six—does it still feel important? I once waited a year to pull the trigger on a pricey leather backpack, which I’ve worn regularly over the decade since. It’s now time to get it reconditioned, and I can’t wait to see this old friend looking its best again. After I learned that (for me) nothing beats a tight-back sofa and bought one that’s perfectly sloped for reading and long enough for napping, there was only one option when the seating began to sag from years of use: I reupholstered it, even though that meant living without for 6 weeks when a brand-new one could have been delivered pronto.

A passion for upkeep, however, hinges on good choices at the outset. Is what you’re considering made of materials that will hold up? Or is it designed for obsolescence with parts that are impossible to replace and construction that’s bound to fail in ways that, once broken, can never really be fixed?

Beyond its physical qualities, what counts is how you’ll feel about a product down the road. So much of what we encounter is designed to appeal to us in the moment, with colors and features that make what we already have seem old hat—but quickly become passé themselves. Think about the warp speed with which trends in fashion, particularly women’s fashion, change. (Where’s that cold shoulder top now?)

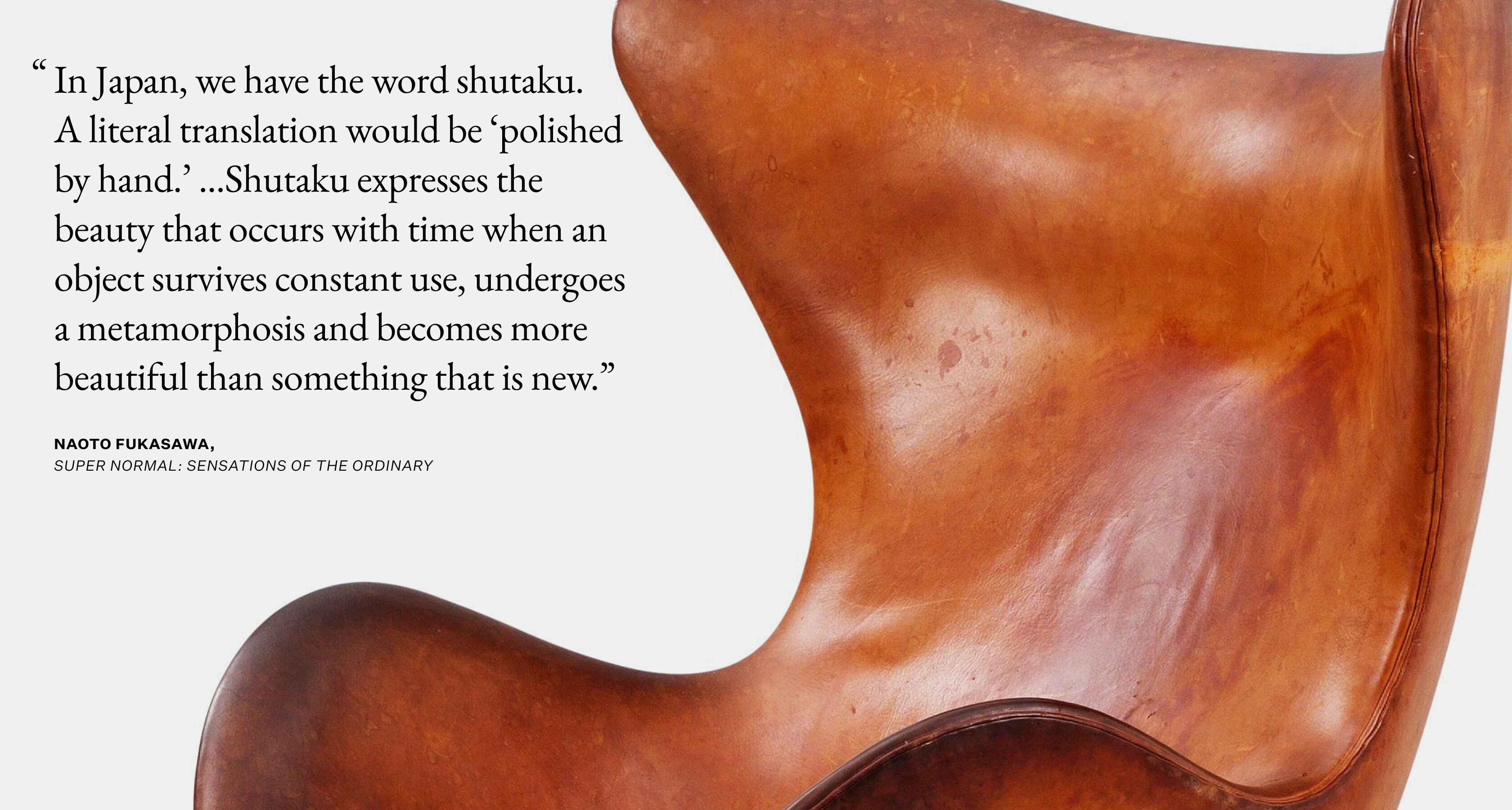

Designers Naoto Fukasawa and Jasper Morrison coined the phrase “super normal” for products that do their job so naturally and effectively we wouldn’t want to live without them. In other words, how they work in our lives is more important than how they look or who created them. In the 1970s, Dieter Rams addressed similar criteria in his principles for good design, which stipulated that to be good a product must be useful and long-lasting, “even in today’s throwaway society.” (He was grappling with his profession’s contribution to the problem.)

Quality can be pricier but choosing wisely matters more than what you spend. Check a product’s details to know what you’re getting. Look at secondhand shops to find deals—and extend the life of things that have already been made. In the end, paying a little more up front may be worth it if the item has real staying power. Above all, you should feel a connection to what you buy—that’s the surest way to ditch the disposable mindset.

“If you want a golden rule that will fit everybody, this is it: Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.”

—William Morris, designer who helped inspire the Arts & Crafts Movement

PATINA

The tyranny of the new plagues us in more ways than one. Yes, a pushy marketplace doggedly baits us with the latest goods, but mass production has also ushered in a psychological intolerance toward anything faded or worn. Why wouldn’t you replace something tired if you easily could?

But it is possible, even pleasurable, to find beauty in the scars on a cutting board or a wine stain on a sleeve, rather than seeing them as imperfections. One is a memory of meals enjoyed, the other evidence, perhaps, of a celebratory moment. Try letting them stand as a record of your experiences, like creased black-and-white family photos.

Emily Spivack documented the memories behind the clothes people can’t part with in her book and Netlfix series, both called Worn Stories. In the book, MIT professor Sherry Turkle shares that she loves an old purple top precisely because of the holes mice chewed in it, which remind her of a night spent holding her infant daughter. (Her daughter threw up the mac ‘n’ cheese that drew the mice to the laundry.)

There's a craft movement around treating repairs as part of the story—additions to, not subtractions from, an item’s aesthetics. I first tried my hand at this with writer Jennifer Kabat’s instructions for turning “lemons into lemonade” when you find that moths have eaten holes in your sweater. Using a buttonhole stitch and bold red thread against a gray knit, she made the mends a focal point of her now one-of-a-kind design. My own sweater was navy, and I leaned way in, landscaping the formerly sober surface with radiant pink eyelets. After that, I found myself loving the piece more than I had when it was in pristine condition. As eye-opening as the exercise may have been for me in 2006, visible mending was hardly groundbreaking in the grand scheme of things.

Japanese sashiko—a type of embroidery that covers patchwork repairs with decorative stitches—dates to the 1600s. Another Japanese practice that's been around for at least as long, kintsugi highlights repairs in pottery with metallic lacquer. Today menders like Katrina Rodabaugh and Kerstin Neumüller are referencing these traditions—both the techniques and the philosophical underpinnings—as they seek to change our relationship to the material world.

This thinking goes hand in hand with the right-to-repair crusade that would put an end to designed-in obsolescence in favor of a more sustainable, more ethical way of making and owning things. Whether it’s learning to fix your own stuff, getting help from someone who knows how or fighting for the fundamental right to repair what you buy, there’s a group of people invested in making it happen.

Living with older things is hardly a sign of making do—it's a testament to their worthiness.

“We come to appreciate an object through using it, and the more we use a good object, the more we are able to appreciate its qualities, and we may discover its beauty not in just how it ages but in how we age with it.”

—designer Jasper Morrison, Super Normal: Sensations of the Ordinary

Does all this deliberation sound dull in a shopping-haul world? I’d contend that the kind of slow-burn satisfaction that keeps on giving for many years is even better than the instant gratification of an impulse buy. Thoughtful choices—purchases you plan for, invest in and take the time to care for—are the ones you really value, no buyer’s remorse involved. I know I appreciate my backpack and sofa all the more because I waited for exactly what I wanted.

So before you click “add to cart,” ask yourself, do you really need another pair of pants? We’re just as happy if the answer is no, because EILEEN FISHER’s mission is to make clothes you’ll wear often—and for a long time. Whenever you are ready for that next pair, we’ll be right here.