Chasing Timelessness. Lessons from Modern Design.

Bernard Hoffman/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

How can designers disrupt the maddening pace of fashion trends? The answer is simpler than you might think.

Fashion changes with the times: miniskirts one moment, maxis the next. It feeds our fleeting tastes and mirrors cultural shifts.

Timeless design, on the other hand, lasts year after year—be it a chair or a trench coat—because people continue to want it. The public ultimately decides what has staying power. So how does a clothing designer, working in the uneasy space between fashion and timelessness, set out to achieve what she can't possibly control?

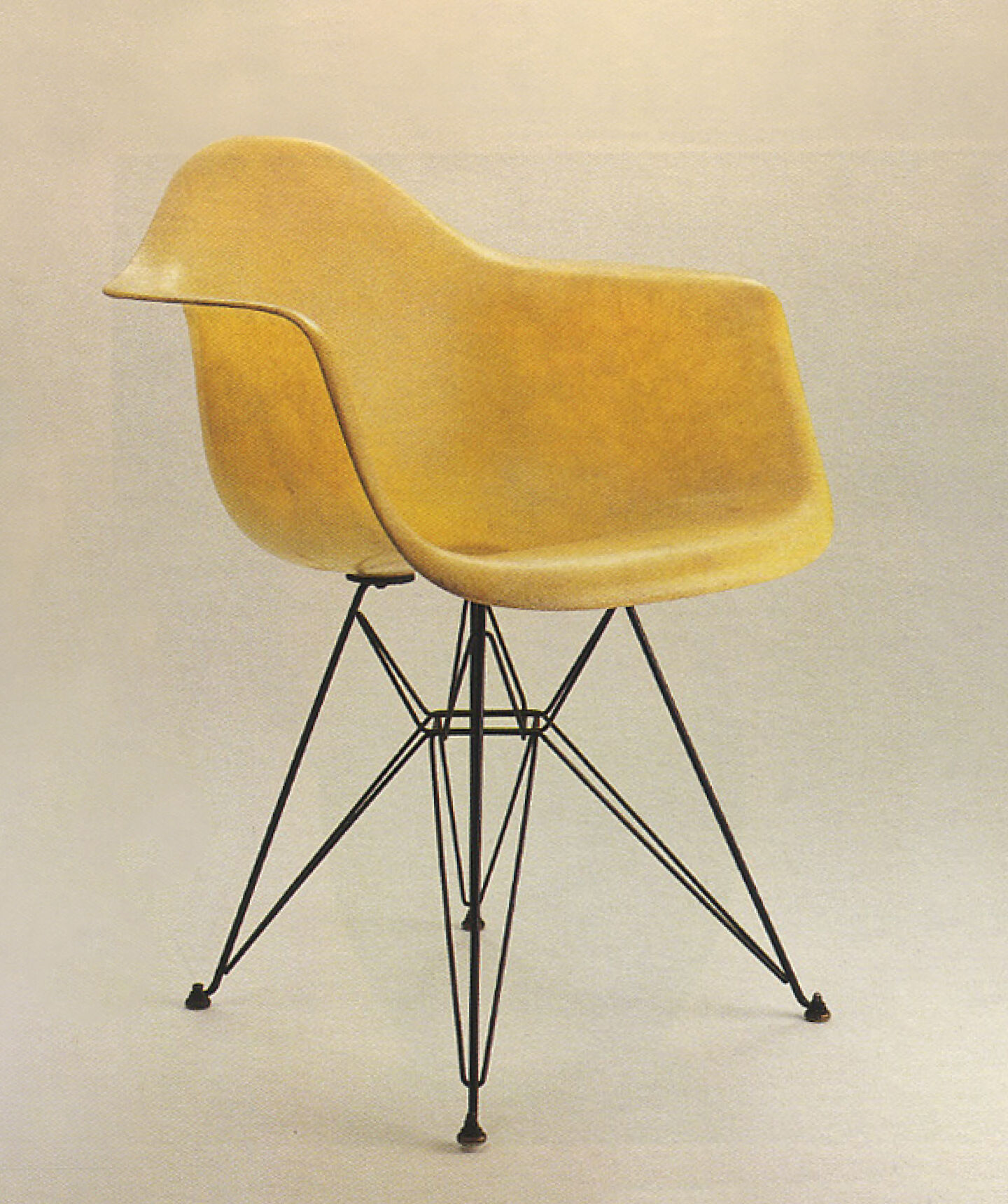

Just what is timeless design? Is it a Baroque chair, circa 1700, still desirable for its curves and carvings? Or Herman Miller's Molded Plastic Side Chair from 1950, designed by Charles and Ray Eames without a single frill?

It's both, of course, for the simple reason that they've stood the test of time. Today, the originals are collectible and knockoffs abundant. Magis makes its mock-antique Proust armchair out of molded plastic, and Memoky.com (props for candor) even offers its Eames-lite Eiffel with your choice of original leg styles for those who don’t want to spring for the real deal.

Left: Eames Molded Plastic Side Chair with an Eiffel base, originally designed in 1950.

Right: Louis XV white and blue-painted fauteuil by Nicolas Heurtaut, circa 1750.

Photo courtesy of Dalva Brothers.

But if timelessness is, by definition, "not restricted to a particular time or date" (so says Merriam-Webster), then does either chair fit the bill? You can't mistake a Louis XV: the handcrafted techniques and romantic motifs are dead giveaways.

It's a bit harder to pinpoint when the Eames chair was created. Granted, we're a few centuries closer to the article in question, but Modernism specifically sought to strip design of its chronological cues. Design historian Jonathan M. Woodham describes the movement as "a radical shift away from the prevalent climate of historicism and the ephemerality of fashion styling." In other words, it skips the telltale decorations.

The Modernists wanted to erase the traces of history from design: Timelessness was merely the happy outcome. When Eileen Fisher started her company (in the heyday of the eighties excess, no less), timelessness was her objective, and she aimed squarely at it by designing clothes pared down to their "simple, pure essence."

In the end, all design is of its time. Take the shell of those Eames chairs: they were originally stamped in metal for a Low-Cost Furniture Design competition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1948. The switch to fiberglass came two years later, when the Eameses sourced a material never before used in furniture. "We've never designed with the idea of fitting into fashion," Charles said during a 1956 interview on NBC. "In the case of the plastic chairs, the object was to take a high-performance material developed during the war and try to make it available to households at non-military prices."

If the Eameses were to make the chair today, they might opt for another material altogether. In fact, Herman Miller swapped to polypropylene around 1990: It has the matte finish Charles is said to have wanted, is less brittle than fiberglass, gets molded entirely by machine and can be recycled.

By embracing the materials and technologies at hand, Modernism, like any other style, reflects its era. It's just that simplicity has a better poker face.

Bel Air Easy Chair by Memphis Milan, 1982. Vitra Design Museum, photo: Jürgen Hans

Ask yourself which feels more current, the Eames chair or one designed more than thirty years later by Memphis, which took a shot at kicking Modernism to the curb? (Picture the cover of Duran Duran's Rio album or the set of Pee-wee's Playhouse. You get the gist.) Memphis reacted to what they saw as the tyranny of good taste, but an eighties affection for gaudy tones, kitschy pattern and geometric assemblages means Memphis designs now feel like exactly what they are—relics of days gone by.

Compare that untimely fate to the legacy of one particularly persistent typeface, Helvetica, designed in 1957. It's the clear, friendly sans serif font that shows up everywhere from New York City subway signage and IRS tax forms to the logos for Crate & Barrel, Greyhound, Sears, Muji and The North Face. Massimo Vignelli used it in 1966 for his half-red-half-blue American Airlines logo. "It's the only airline in the last 40 years that has not changed their identity," he said in the 2007 documentary Helvetica.

Michael C. Place, creative director of the London-based communications design firm Build, sang the simple typeface's praises in the same film: "It's been around 50 years, coming up. It's just as fresh as it was then."

That's a pretty good working definition of timeless design.

When I see the words "simplicity" and "design" side by side, my mind goes straight to Dieter Rams, the German industrial designer revered for the lucid forms he created at Braun. (Many an Apple product is just a Braun design with a fresh coat of titanium.) Browsing Rams's portfolio, I was floored to find the Braun Citromatic juicer I'd bought myself some fifteen years ago—didn't know it was by Rams. I also didn't know it was designed in 1972. And I'll bet the person who buys one tomorrow won't have a clue they're getting a Nixon-era appliance either.

All that's changed over the past forty years are the Citromatic's electrical components. Outside, it looks exactly the same—like the classic hand juicer (shallow dish, reamer perched in the center) atop a spouted pedestal. Take a moment to process that: a design released the same year the VW Beetle became the world's best-selling car looks every bit as contemporary today as it did then.

Citromatic Deluxe Citrus Juicer by Dieter Rams and Jürgen Greubel for Braun, originally designed 1972.

Turns out, the Citromatic was also Apple designer Jonathan Ives's first encounter with Rams, discovered in his parents' kitchen. "No part appeared to be hidden or celebrated, just perfectly considered and completely appropriate," he writes in the monograph Dieter Rams: As Little Design as Possible.

That's all well and good for a juicer, but what does it mean in the context of fashion, the very definition of which is "the prevailing style (as in dress) during a particular time?"

Eileen began her company with an idea straight from the pages of the Modernist playbook, one that pushes back against fashion's fickle nature. "I started EILEEN FISHER for a very personal reason: I was having trouble getting dressed," she says. "At the time I was working as an interior and graphic designer. In my mind I kept seeing these simple shapes for clothes. I knew they had to be beautiful colors, great fabrics and have certain shapes and proportions that worked together." She felt styles that transcended the fashions would make it easier for women to get on with their lives.

Trend is surprisingly easy to master. Zara has it down to a science: The company is a model of agile production, able to design and deliver a garment to the store racks in just two weeks. Its sales staff doubles as a data feed, sleuthing out what catches customers' fancy and reporting back to headquarters in real time, so the craveable is always available. Zara is the race leader in a highly competitive warp-speed fashion cycle that "changes the rules of what we're supposed to wear constantly," says Elizabeth Cline, author of Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion.

EILEEN FISHER aims to create clothes people will wear more than a few months from now. But how does a clothing designer go about making a style that will last years, perhaps decades, definitely longer than the next fad? Especially when the company is open to passing influences, so long as the results stay true to its design values.

“In my mind I kept seeing these simple shapes for clothes. I knew they had to be beautiful colors, great fabrics and have certain shapes and proportions that worked together."

Design Director Julie Rubiner takes her cues from the archives. Knowing what works for EILEEN FISHER gives her the freedom to experiment. "The past doesn't sound like inspiration, but it is, especially when I'm playing with new yarns and new stitches," she says.

It's her job to design clothes that walk the line between timely and timeless. "If I'm working with something dimensional, I'll use a shape we know our customer has always gravitated to. Or I might take one of our iconic shapes and add a detail—a mock neck, a slit at the ankle—that makes everything you wear it with feel fresh. The end result is so simple and clean, but it's much more complex to do than just mimicking a trend for the season."

Likewise, there's an MVP roster of fabrics to pull from. EILEEN FISHER still favors natural fabrics like linen, cotton, silk and wool. Consider the serious hang time (we're talking centuries) of these four fibers.

Our iconic shawl collar coat, one of Eileen's earliest designs. A style we return to year after year.

The basic building blocks for EILEEN FISHER are always the same: shapes, fabrics and neutral colors that appear on the line again and again. It's what's done with them that changes. "Young designers come into the company and reinterpret things," Eileen says. "Maybe the proportions are a little different, maybe the shapes are a little different. Their work has a freshness, but it still has the inherent values of the original designs."

The touch of trend—a sequin here, a higher neckline there—doesn't define the clothes, which also dare to be unfashionable. Eileen's beloved box-top is voguish now but not so in the nineties, yet it never left the line. It's essential to her modular way of thinking about fashion: a series of beautiful shapes that drop onto a simple foundation—much like the plastic shell of the Eames chair and its range of bases (dowel, stacking, Eiffel, rocker). That's just plain Modernism, written in cloth and stitches.

Turns out, there is a method to transcending fashion's maddening pace. It's really quite simple.